Mastering & The One (Not So) Secret Trick To Rule Them All

- Apr 26, 2018

- 4 min read

Make a notch using a bell filter at 250Hz… is precisely not it. :) Way back when, when I’d first acquired an unquenchable thirst for soaking up any and all audio production related information I could get my hands-on (and information had been way scarcer in the pre-YouTube days), I became enchanted with all sorts of tricks, quantifiable and precise rules akin to ‘cut this many dB here’, and a dose of ‘alwayses’ and ‘nevers’ (‘always start by inserting a high pass filter on every track’; ‘never use an EQ for boosting’, … you know what I mean!). While a lot of these prescriptions are by no means arbitrary and have brewed over the decades as a sort of a statistical result of common issues popping up in mixes and their respective remedies, they are but a starting point — an initial nudge or a route to explore —, and then assess. It is the assessment part of the equation that all too often goes undiscussed, although it is as much, if not more important that the technique that preceeds it.

So while the majority of music production articles will focus on quantifiable techniques (and I will probably stray in that direction at various points in some future posts), I would like to focus more on the underlying principles. As technology and tools evolve, so do the techniques. The foundational principles (ie. your mind’s interaction with ‘the machine’) remain.

Feed a man a fish — teach a man how to fish kinda deal.

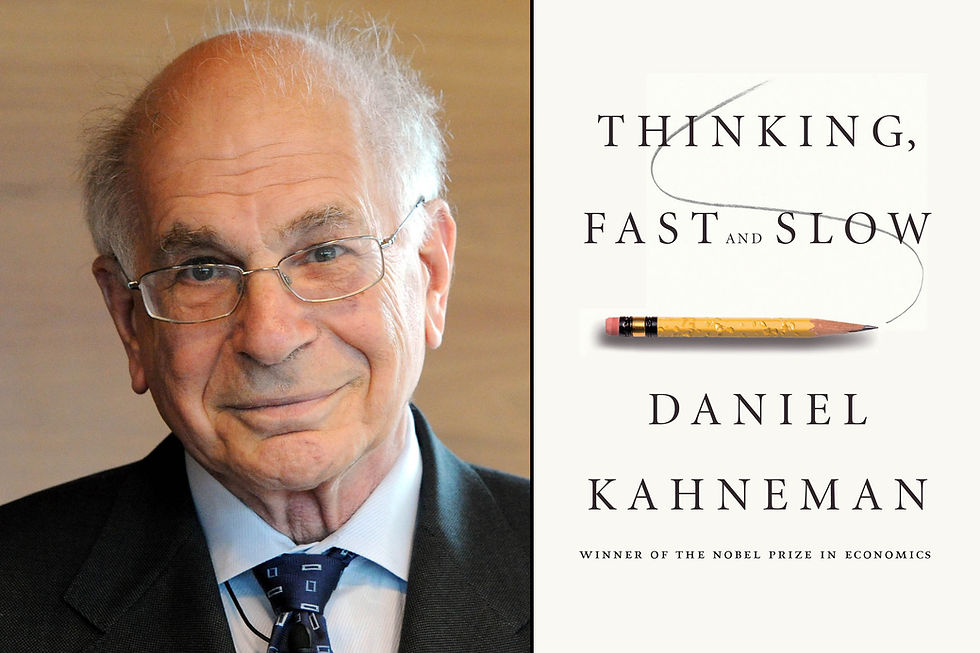

So what IS the big deal? Enter Kahneman…

As much as I’ve developed a healthy dose of contempt for click-bait-laden, flashy headlines promising the music production technique equivalent of six-pack abdominals in 6 days, I am, in all honesty, rather serious in calling this deceptively simple and obvious technique a true superstar, a universal low-level kind of principle to help one make better decisions while mastering (and beyond).

The more time we spend doing this thing — and I may as well extend this to any artistic endeavour where quantifying the output of your hard work is very problematic or downright impossible… the more time you spend ‘in the game’, the more you may end up realising how we fall prey to all sorts of wicked tricks our mind plays on us when it comes to judging whether what we’re doing is to the benefit, or the detriment, of the entire piece.

Whether producing a tune or mastering a song, which, albeit a lot more technical, leaves a great deal of room for the manifestation of individual aesthetics, we fall victim to a sunk-cost fallacy bias. Chances are you read the incredible book by Daniel Kahneman on the very topic of cognitive biases. How on earth might you ask is some woo-woo psychology related to mastering? An uber great deal I’d say! The Nobel prize winning Kahneman (so not really woo-woo at all) really hits home when describing the sunk cost fallacy, which shows you that our decision-making is corrupted by the time we have invested into our work. What this means in simple terms is, the longer you’ve worked on a tune or had been finely crafting a master using a dozen laser-precision 0.2dB adjustments, the harder it becomes for your mind to let go and be able to realise that, just perhaps, scraping it all and doing one simple adjustment works way better in the grand scheme of things.

So, without any fanfare, enters, at last, the not so secret trick to rule them all: just bloody close your eyes (when judging what you’re doing with your master).

This was quite possibly very underwhelming. Effective things often are simple. But wait, I believe matters must get more granular to be effective here: in order to free yourself from the sunk cost-laden attachment to one settings of a processor, use your DAW’s function to A-B between two settings (let’s say we are talking EQs here).

—Place your mouse cursor (or use a keyboard shortcut) over the button that toggles between them.

—Only now close your eyes, and toggle back and forth an arbitrary amount of times.

—At this point, you should have fooled yourself enough to forget which settings had been which.

—Only start listening attentively now, whilst keeping your eyes closed, slowly toggling back and forth until you arrive at the ‘better’ settings.

(—Optional: open your eyes again. ;-)

Digging deeper

There are more obvious caveats to take note of here. Another bias, as strong as the sunk cost fallacy described above, is an extension of the ‘shiny new object’ phenomenon. Our brains are wired to be attracted by novelty (and they stop paying attention to familiarity). An extension of this phenomenon is when you for example tune out the walla chatter inside a bustling coffee place, but if someone suddenly raises their voice above the ‘white noise’ level, it pricks up your hearing. In much the same way, a louder sound will excite your senses more, and you will likely deem a louder settings better. So apart from the above-mentioned technique, do pay attention to first adjusting the output gain of the affected processor’s settings before starting the A-B’ing described above. Another very obvious one I suppose, but it had to be mentioned.

As far as simple-but-effective tips go, this closing hint is very much in line with the others: apart from A-B’ing between two settings of an EQ (or a compressor or what have you), also try to toggle between an inserted processor, and bypassing it entirely. You will learn to accept the sad, sad truth that oh-so many times your beloved EQ or compressor is better left bypassed and looking good in the rack (much sadface).

Stay tuned for more posts. If you enjoyed this one, please do not hesitate to subscribe to the mailinglist and / or drop me a line on what else you’d like to hear on.

With Love -Lukas

Comments